곡선 선택 배너 스톤, 글렌 폭포, 뉴욕, 6, 000–1, 기원전 000년, 줄무늬 슬레이트, 2.7 x 13.6 cm(미국 자연사 박물관 DN/128)

미국 전역의 학교에서 고대 이집트인과 그리스인, 중국인에 대해 배우는 이유는 무엇입니까? 그러나 북아메리카의 고대인들은 그렇지 않습니까? 기원전 6000년에서 1000년 사이에 미국 동부 지역에서는 고대로 알려진 시대에, 수천 명의 유목민 아메리카 원주민이 미시시피 강과 오하이오 강을 따라 여행하고 살았습니다. 오늘날 배너스톤으로 알려진 조심스럽게 조각된 돌. 일반적으로 모양이 대칭이고 중앙에 구멍이 뚫려 있습니다. 19세기 고고학자들과 수집가들은 이 독특하게 조각된 돌들이 “배너”로 공중에 올려진 나무 막대에 놓여 있다고 가정했습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 우리는 여전히 그들을 배너스톤이라고 부릅니다.

곡선 선택 배너 스톤, 글렌 폭포, 뉴욕, 6, 000–1, 기원전 000년, 줄무늬 슬레이트, 2.7 x 13.6 cm(미국 자연사 박물관 DN/128)

배너스톤, 석판처럼 <나> 커브드 픽 글렌 폭포에서, 뉴욕, 신중하게 선택한 돌을 조각한 다음, 드릴, 이 특별한 돌의 중심에는 고대 조각가는 암석이 형성될 때 퇴적물에 묻혀 있는 흔적 화석으로 알려진 것을 형성하기 위해 벌레나 다른 생물학적 요소가 남긴 회백색 표시를 표시하고 강조하는 작은 능선을 조각했습니다. 화석 흔적은 슬레이트의 대칭적인 어두운 자연 밴딩을 가로질러 교차합니다(슬레이트는 두 가지 지질학적 과정에 의해 형성되었습니다. 퇴적 과정과 그 다음 변성 과정) 밝은 갈색에서 짙은 갈색까지 띠의 다른 색상은 암석 구조로 굳어진 퇴적층이 서로 다른 것을 나타냅니다.

커브드 픽 배너스톤(반대), 글렌 폭포, 뉴욕, 6, 000–1, 기원전 000년, 줄무늬 슬레이트, 2.7 x 13.6 cm(미국 자연사 박물관 DN/128)

한편, 돌의 밴딩은 눈에 띄게 다른 패턴을 형성하고, 돌의 양쪽에 서로 다른 퇴적 패턴이 있는 자연적으로 발생하는 슬레이트로 만들어 조각가가 양쪽 면을 하나의 복잡한 구성으로 구성하도록 유도하고 도전했습니다. 슬레이트는 상대적으로 부드러운 돌이며 다른 돌보다 모양과 드릴이 더 쉽다는 점을 감안할 때, 그것은 고대 북미 원주민이 배너 스톤을 만들기 위해 선택한 가장 일반적인 돌 중 하나입니다. 특히 오하이오 밸리에서요.

커브드 픽 배너스톤(상단), 글렌 폭포, 뉴욕, 6, 000–1, 기원전 000년, 줄무늬 슬레이트, 2.7 x 13.6 cm(미국 자연사 박물관 DN/128)

원석이 강에서 닳았거나 산 중턱에서 채석된 것이 발견되면, 조각가는 "해머스톤"으로 알려진 더 단단한 돌을 가지고 쪼개기 시작하고 줄무늬 슬레이트를 갈아서, 현대 학자들이 이 고대 아메리카 원주민 예술 작품에 대한 연구에서 정의한 24가지 고유한 현수막 유형 중 하나에서 작업을 모델링합니다.

Twenty-four different types of bannerstones identified by Byron Knoblock in 1929

Choosing the Curved Pick type, one of several bannerstone forms particular to the Northeast, the sculptor worked their composition to be precisely centered on the two different faces of the banded slate, grinding the “wings” into a raised edge that runs through the dark slate bands, and flattening, shaping, and smoothing the surface around the perforation, further individualizing their finished work. The individuality of each bannerstone in relation to recognizable forms, recognizable to the Archaic sculptor and to those of us studying these stones today, is an intrinsic component of their making and meaning.

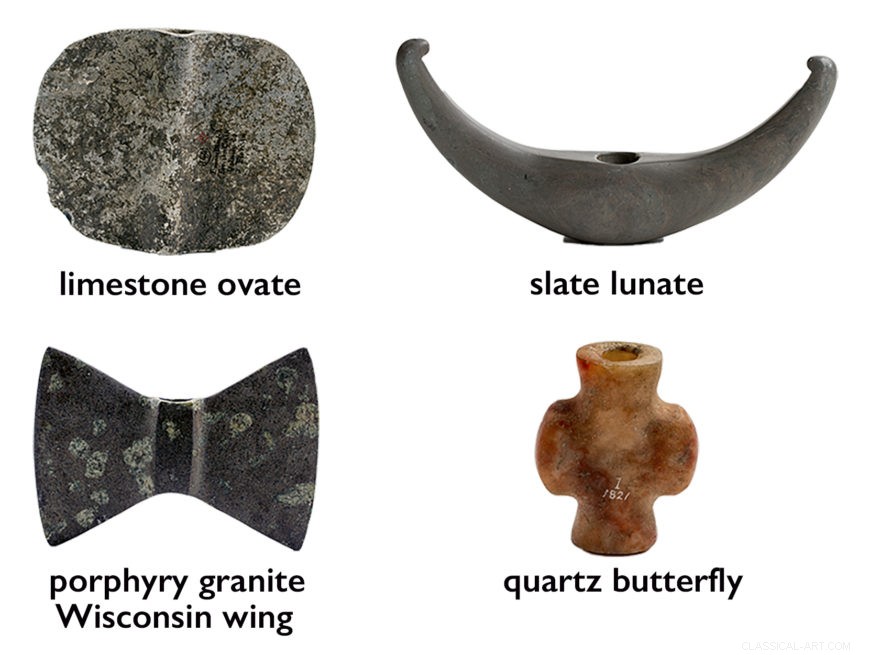

Different types of bannerstones (clockwise from left:American Museum of Natural History d/144 Limestone; American Museum of Natural History 13/105 Slate; NMNH A26077 Porphyry Granite; American Museum of Natural History 1/1821 Quartz)

Bannerstones were made from many types of stone including those that are sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. The sedimentary rock that we see in a limestone ovate bannerstone is the softest, while slate (a metamorphic stone) shows more signs of natural geologic transformation such as banding that we see in a lunate bannerstone. Igneous rock is the hardest and often has embedded elements from various minerals when magma first bubbled up from the core of the earth and cooled. This kind of complex igneous surface is evident in a porphyry granite Wisconsin wing bannerstone. Some bannerstone (like the quartz butterfly) are made out of even harder material made of minerals and crystals that would have been even more time consuming and challenging to carve. The relative hardness of the stone chosen by the sculptor would have an impact on the kinds of bannerstone forms they would or could sculpt. The thin wings of slate and even granite bannerstones could not be carved out of quartz, while the seemingly thick rounded form of a Quartz Butterfly bannerstone might appear unfinished if it were carved in slate.

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, Georgia, 6, 000 – 1, 000 B.C.E., igneous, coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

Unfinished bannerstones

Whatever their shape or relative state of completion, all bannerstones were made using river-worn pebbled hammerstones to peck, 갈기, and polish the surface. Some bannerstones, however, were intentionally left in a partial state of completion known as a “preform” such as a Southern Ovate from Habershan County, 그루지야.

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, Georgia, 6, 000 – 1, 000 B.C.E., igneous, coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, Georgia, 6, 000 – 1, 000 B.C.E., igneous, coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

This bannerstone is partially drilled at the spine on one side with a hollow cane or reed that grow along the banks of rivers, and undrilled at the other side. The reed itself is hollow and when rubbed briskly between the hands with the application of water and some sand, can drill through slate, granite and even quartz. With this stone the partial passing of the reed leaves concentric circles on the inside of the perforation and a small nipple visible here that would fall out the other side when the perforation was complete. The medium to coarse-grained igneous rock is left unpolished, just as the ovate form and perforation are left unfinished. Scholars believe that preforms such as these were often buried in this state, or meant to be finished at a later date by another sculptor in a different location. The kind of granite we see here is unique to this region of the Southeast and so would likely have been valuable as a trade good further west along the Mississippi where there was little or no stone available. By partially completing the Ovate form, even partially drilling the perforation the sculptor of this southeastern stone increased the value of the stone while leaving the finish work to whomever acquired this Ovate in this preform state.

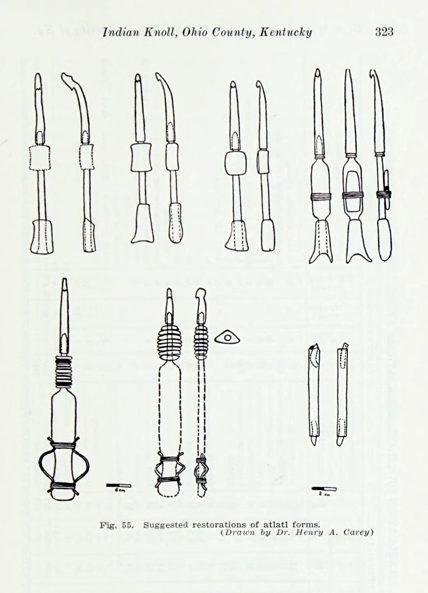

Illustration in William S. Webb, Indian Knoll , 1946 (publication of his 1937 study at Indian Knoll), p. 322

Hunting tools?

How to use an atlatl, here with an arrow (mage:Sebastião da Silva Vieira, CC BY 3.0)

In 1937, William S. Webb, at the University of Kentucky, with his large crew of Works Projects Administration (WPA) workers funded by the New Deal in the 1930s, excavated 880 burials at the Indian Knoll site in Western Kentucky. Amongst these 880 human burials, Webb found 42 bannerstones buried with elements of throwing sticks known as atlatls. Webb proposed that the bannerstones were weights that had been made to be placed on the wooden shafts of these hunting tools. The first inhabitants of Eastern North America used atlatls instead of the bow and arrow until 500 C.E. The two-foot long shaft of the atlatl could propel a six-foot spear and point great distances with accelerated speed and accuracy. It is a tool invented and used in Eurasia and Africa as early as 40, 000 B.C.E. and ubiquitous throughout the Americas after it began to be inhabited thousands of years later.

Though many scholars after Webb, including myself, agree that many bannerstones were likely carved and drilled to be placed on atlatl shafts, this particular hypothesis raises as many questions as it may appear to answer. For instance why would these Native American sculptors dedicate so much time to an atlatl accessory that appears to have nominal if any effect on the usefulness of the tool? This raises other unanswered questions about the usefulness of beauty and how aesthetics, pleasure, and play are significant, though often overlooked, elements of ancient Native North American art.

Partially destroyed double crescent type bannerstone (American Museum of Natural History DM 333)

NAGPRA

Since Webb’s 1936 excavation at Indian Knoll, Kentucky, remains and belongings of Native Americans are no longer simply there for the taking for the collector’s shelf, college laboratory, or museum case. Especially with the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (known as NAGPRA), funerary remains of Native Americans (bodies and objects placed with these bodies in burials) are protected from being disturbed or excavated unless permissions have been granted by Native communities culturally affiliated with the burials. [1] Native American funerary objects already in federal agencies or museums and institutions that receive federal funding are to be made available to culturally affiliated communities that have the right to request their repatriation. Whatever the aims of post-Enlightenment science or the elucidating potential of the exhibition of artworks may be, these ideological motivations must be negotiated with and in light of the desires, memories, practices, and philosophical underpinnings of the Native American people and their descendants who often buried their dead with bannerstones and other burial remains.

Currently the William Webb Museum has recently removed all photographs of the 880 burials and 55, 000 artifacts that Webb excavated at Indian Knoll in 1936 and will no longer allow scholars to study these remains “until legal compliance with NAGPRA has been achieved.” What “legal compliance with NAGPRA” specifically means for the remains including bannerstones excavated at Indian Knoll is profoundly complex. No living communities of Native Americans trace their direct line (in legal terms, known as “lineal descendants”) to the Archaic people who built this shell mound in which they buried their dead along with valued objects including broken and unbroken bannerstones. With the ratification of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Shawnee and Chickasaw communities that lived in Western Kentucky in the 19th century were forced to move west to Oklahoma. [2] How the William Webb museum will choose to adhere to NAGPRA and what they will do with burial remains from Indian Knoll will set a precedent unfolding into the present about how to collaborate with living Native American communities (even those who are not “lineal descendants”), and how to mindfully regard the past lives of the Ancient people of North American, their human remains along with the multitude of things they made, valued, and arranged in and outside of burials.

Intentionally broken?

Since the 19th century, many bannerstones were found in ancient trash piles known as “middens” as well as ritual burials of things known as “caches” and many more in human burials in subterranean or earthen mound architecture. A large number of bannerstones have also been found broken in half at the spine where they are most fragile due to the thin walls of the drilled perforations.

Broken butterfly type bannerstone (American Museum of Natural History 20.1/5818)

Kill hole in the center of a plate with a supernatural fish, 7th century, Late Classic Maya, earthenware and pigment, 10.5 x 40.6 x 40 cm, Guatemala (De Young Museum)

The intentional nature of these acts of breaking are evident in the placement of pieces together with no sign of wear along the broken edges, carefully arranged with other valuable objects. Archaeologists and historians of the ancient art of the Americas amongst the 8th century-Maya (of Mesoamerica) or 12th-century Mimbres art (of what is today the southwestern U.S.) have often identified this practice as “ritually killing” the object before burial. Though these bannerstones in most cases were intentionally broken by the very people who carved them (most likely just before burial), the meaning and purpose of this act further reveals something about the conceptual and even poetical importance of these sculpted bannerstone forms. Rather than “ritually killing, ” bannerstone makers as well as other artists of Ancient America appear to be repurposing artworks, using them in one way at first, then reconceptualizing them to accompany their dead underground, as a kind of memory-work for the living not entirely unlike the carefully constructed exhibition spaces or storage units of our museums. For the Indigenous people of the Americas the earth itself was often seen as a repository for cultural and personal objects, an underground space that was curated with things that continued to have meaning for the lives of communities for decades and even centuries.

Notes:

[1] More on NAGPRA can be found here and here. [2] Read about the Indian Removal Act at the Library of Congress.