책 인쇄는 공동 노력이었고, 여기에서 인쇄기를 위한 책을 준비하는 다른 사람들을 볼 수 있습니다. 얀 콜라에르트 1세(Joannes Stradanus) 이후, “책 인쇄의 발명, " 에 현대의 새로운 발명품(Nova Reperta), 플레이트 4, 씨. 1600, 종이에 조각, 27 x 20cm(메트로폴리탄 미술관)

인쇄기는 초기 근대 세계 역사상 가장 혁명적인 발명품 중 하나였습니다. 15세기 독일의 금세공인이자 출판사인 반면, 요하네스 구텐베르크, 이미지와 텍스트의 대량 생산을 가능하게 하는 기계식 인쇄기를 만든 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 활자 기술은 훨씬 더 일찍 동아시아에서 최초로 개척되었습니다. 11세기 초 중국에서는 장인 Bi Sheng은 구운 점토로 개별 한자를 만들어 활자 체계를 만들 수 있다는 것을 발견했습니다. 나중, 13세기 한국에서는 최초의 알려진 금속 가동형이 생산되었습니다.

금속활자로 인쇄된 세계에서 가장 오래된 현존하는 책의 페이지들, 대승려의 선교집 , 1377, 24. 5 x 17 cm(프랑스 국립도서관)

실크로드를 통해 동아시아와 유럽의 문화 교류와 교류 확대, 13세기에 시작하여, 이러한 인쇄 혁신의 확산을 이끌었습니다. 물론, 1400년대 중반, 구텐베르크는 동일한 텍스트 소스와 시각적 표현을 여러 개 인쇄하기 위한 기계적 프로세스를 고안하는 데 중요한 위치에 있었습니다. 어느, 휴대 가능하고 보다 저렴한 용지 지원 덕분에 널리 유통될 수 있음을 의미하며, 디지털 이전 시대에 초기 매스커뮤니케이션 모드로 사용되었습니다. 활자의 도입과 함께 판화의 출판은 지식과 사상의 교차 문화 교류를 위한 전례 없는 가능성을 제공했으며, 뿐만 아니라 예술적 스타일과 디자인.

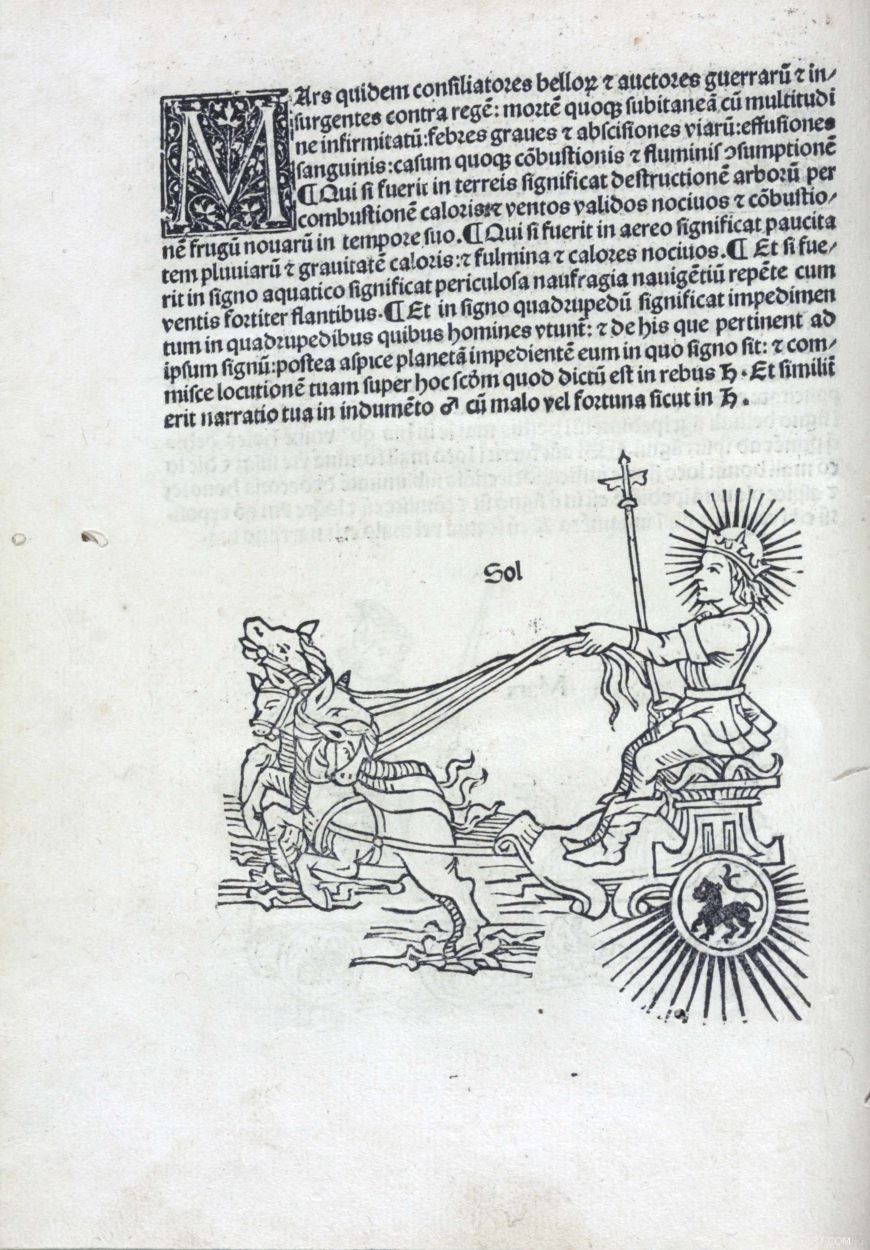

이 삽화는 Erhard Ratdolt가 출판한 책에서 가져온 것입니다. 아우크스부르크 출신의 초기 독일 인쇄업자, 그리고 73개의 목판화로 설명되어 있습니다. 여기서 우리는 "Sol" 또는 "Sun, "알부마사르에서, 플로레스 점성술 (Augsburg:Erhard Ratdolt, 11월 18일, 1488), 이미지 22(로젠발트 컬렉션, 희귀 도서 및 특별 컬렉션 부문, 국회 도서관)

<강한> 예술의 민주화

15세기 이전에는 제단과 같은 예술 작품, 초상화, 그리고 다른 사치품은 주로 부유한 후원자의 거주지와 교회에서 발견되었는데, 그 이유는 이 절묘한 물건을 의뢰할 재정적 자원을 가진 사회 엘리트와 종교 지도자들이었기 때문입니다. 재생산 가능한 인쇄 형식과 증가하는 종이 가용성으로 인해 중산층이 증가했습니다. 그림이나 조각상을 구입할 수단이 없었을 수도 있는 예술적 표현을 수집할 수 있는 기회. 대규모 프로젝트는 여전히 부유한 후원자들에 의해 자금을 지원받았지만, 대부분의 인쇄물은 투기로 구매되었습니다. 결과적으로, 우리는 다양한 수집가에게 어필했을 인쇄물에 묘사된 다양한 주제를 봅니다. 예를 들어, 과거를 연구하려는 욕망, 문학, 초기 현대 유럽 전역의 도시에서 과학은 판화 제작자가 고대 역사의 표현을 예술 시장에 공급하도록 장려했습니다. 고전 신화, 그리고 자연의 세계.

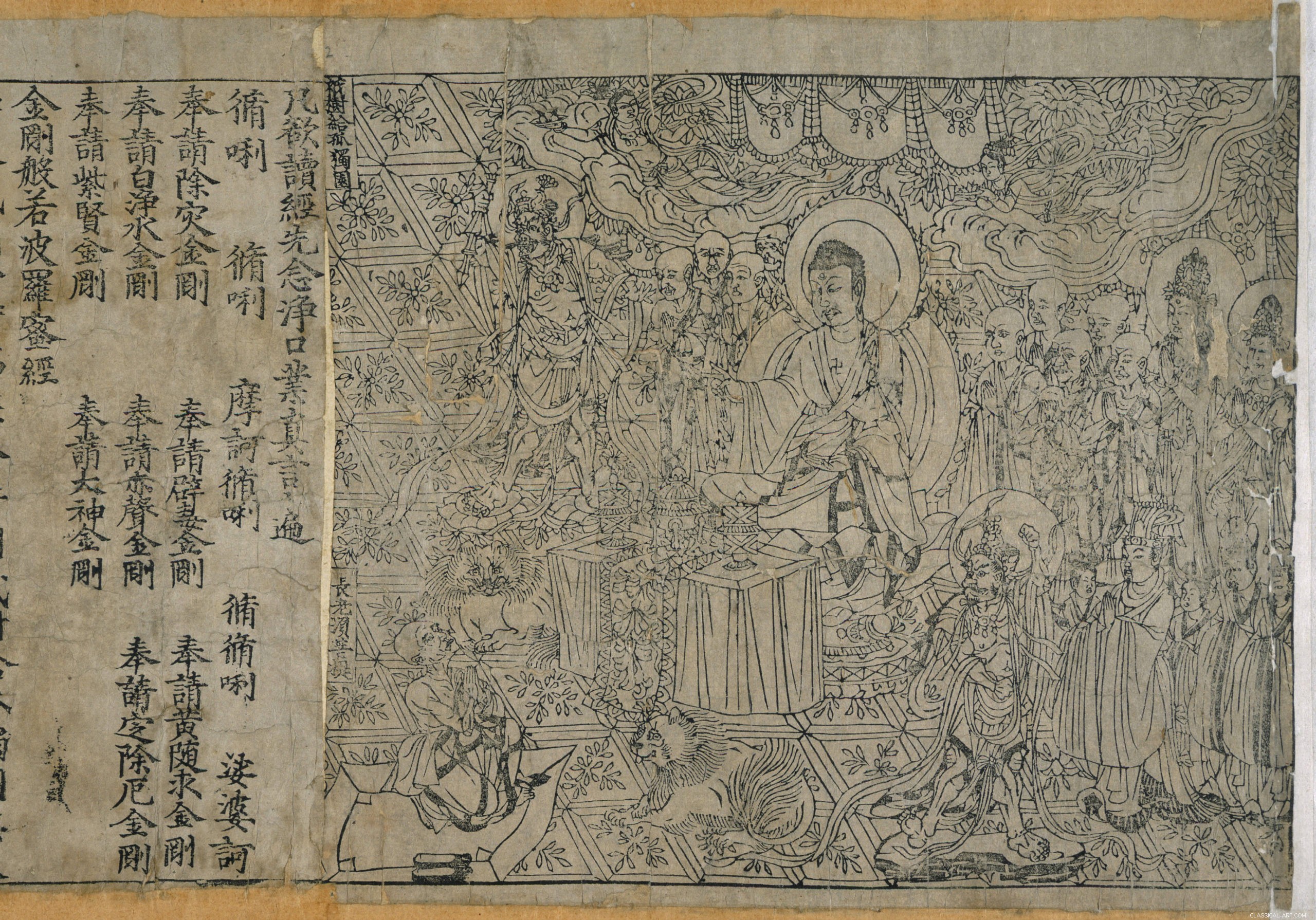

금강경 , 868, 목판 인쇄 두루마리, Mogao (또는 "Peerless") 동굴 또는 "천불의 동굴에서 발견, ” 실크로드를 따라 4세기부터 14세기까지 주요 불교 중심지였다(영국 도서관)

<강한> 목판화

판화의 가장 오래된 형태는 목판화입니다. 일찍이 중국의 당나라(7세기 초), 목판은 직물 조각에 텍스트를 인쇄하는 데 사용되었으며, 그리고 나중에 종이. 8세기까지, 목판 인쇄는 한국과 일본에서 자리를 잡았습니다. 서면 자료를 인쇄하는 관행은 동아시아에서 훨씬 오래된 전통의 일부이지만, 목판을 사용하여 인쇄된 이미지를 제작하는 것은 유럽에서 보다 일반적인 현상이었습니다. 14세기 후반 독일에서 시작하여 네덜란드와 스위스 알프스 남쪽으로 이탈리아 북부 지역으로 퍼졌습니다.

초기 목판화는 종종 종교적 주제를 보여줍니다. 여기에서 우리는 죽은 아들을 안고 있는 성모 마리아를 봅니다. 예수. 남부 독일, 스와비아, 피에타 , 씨. 1460년, 목판화, 수채화로 채색한 손, 38.7 x 28.8 cm(클리블랜드 미술관, 클리블랜드)

페트루스 크리스투스, 여성 기증자의 초상화 뒤의 벽에 프린트가 걸려 있는 책 앞에 무릎을 꿇고(세부 사항), 씨. 1455년, 패널에 오일, 41.8 x 21.6 cm(국립미술관)

구텐베르크가 인쇄기를 발명한 후 15세기 후반에, 목판화는 활자로 만든 글을 묘사하는 가장 효과적인 방법이 되었다. 결과적으로, 마인츠와 같은 유럽의 도시, 독일과 베니스, 처음에 판화가 자리를 잡은 이탈리아는 책 제작의 중요한 중심지로 발전했습니다. 기계식 인쇄기를 사용하여 종이에 이미지를 인쇄하는 유럽의 방법은 16세기에 동아시아에 전파되었으며, 그러나 몇 세기 후 일본의 에도 시대에 유색 목판화(우키요에 판화)가 대량으로 생산될 때까지 예술적 목적으로 널리 채택되지 않았습니다.

초기 유럽의 느슨한 판화 목판화는 주로 기독교 주제를 묘사하며, 상대적으로 저렴한 경건한 이미지로 사용됩니다. 오늘날 박물관은 인쇄물을 기후 조절 상자에 보관하여 미래 세대가 즐길 수 있도록 보존하지만, 15세기와 16세기에 그들은 여행 중에 접혀서 순례자들에 의해 운반되었습니다. 책의 내부 표지에 잘라내어 붙이기, 또는 집의 벽에 압정. 따라서, 지속적인 사용으로 종종 파괴되기 때문에 초기 목판화는 거의 남아 있지 않습니다. 아직, 현존하는 주요 목판화는 이 초기 유형의 인쇄물의 문체적 특성을 보여줍니다.

이 목판화는 화재에서 살아남았습니다. 아기 예수를 안고 있는 마리아의 모습, 성자들과 마리아의 삶의 장면들로 둘러싸여 있습니다. 무명의 15세기 판화 제작자, 불의 마돈나 , 1428년 이전, 목판화, 손으로 물감을 칠하고, 크기를 알 수 없음(산타 크로체 대성당, 포를리, 이탈리아)

예를 들어, 두 개의 목판화( 피에타 남부 독일과 15세기 초 이탈리아에서 만들어진 불의 마돈나 화재에서 살아남은 것으로 추정되는 건물이 있던 건물이 파괴됨) 두 그림 모두 두꺼운 윤곽선으로 렌더링된 기타 경치 요소를 전시합니다. 이 이미지는 최소한의 음영과 패턴이 특징이며, 수집가가 종종 손으로 페인트를 칠하여 구성의 감정적 인 호소력을 향상시키는 스텐실 디자인과 유사합니다. 이것은 그리스도의 상처에서 피가 떨어지는 것을 나타내는 붉은 줄무늬의 페인트와 함께 볼 수 있습니다. 피에타 인쇄.

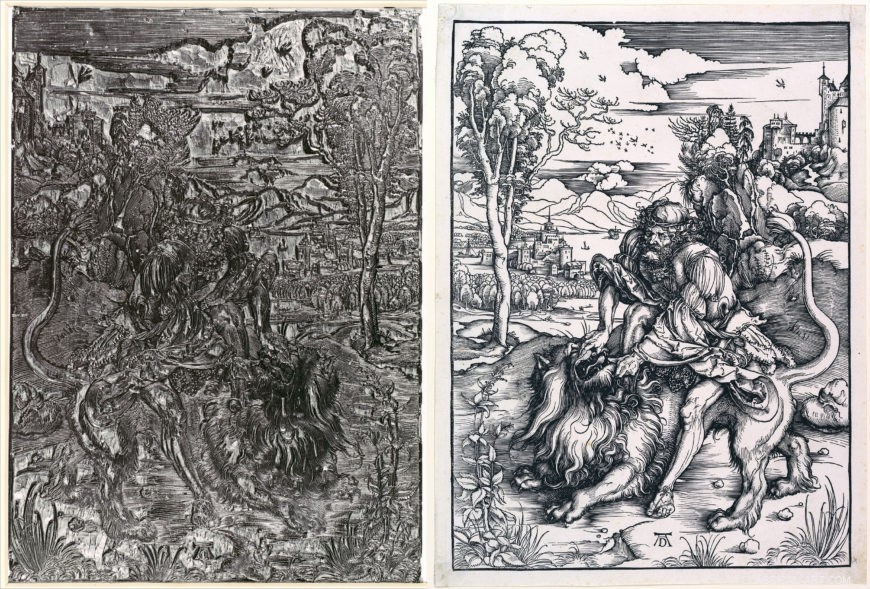

왼쪽:알브레히트 뒤러, 목판 삼손과 사자 , 씨. 1497-1498, 배나무, 39.1 x 27.9 x 2.5 cm(메트로폴리탄 미술관); 오른쪽:알브레히트 뒤러, 삼손과 사자 , 씨. 1497-1498, 목판화, 40.6 x 30.2 cm(메트로폴리탄 미술관)

한 현대 예술가가 휴대용 가우저를 사용하여 목판 디자인을 일본 합판으로 자르고 있습니다. 합판의 도색면에 분필로 도안을 스케치하였습니다(사진:Zephyris, CC BY-SA 3.0)

일종의 구제 절차, 목판화는 매트릭스의 융기된 표면에 잉크를 칠하여 생성되며, 수동 또는 기계적(인쇄기) 압력을 사용하여 블록을 종이에 눌렀을 때 구성의 거울 인상을 줄 것입니다. 고무 스탬프는 릴리프 인쇄의 현대적인 예입니다. 나무 블록에 디자인을 만들려면 예술가는 칼이나 가우징을 사용하여 인쇄할 선과 모양 사이의 나무 부분을 잘라냅니다. 나무 부분을 잘라낼 때, 인상을 만들기 위해 압력을 가할 때 돌출된 선이 너무 가늘게 만들지 않도록 주의해야 합니다. 이것이 초기 목판화가 대담한 윤곽을 가진 디자인을 특징으로 하는 이유입니다.

릴리프 프로세스는 판화의 주요 유형 중 하나입니다. 목판화를 만들기 위해서는 예술가는 매트릭스의 융기된 표면에 잉크를 칠하고, 수동 또는 기계적(인쇄기) 압력을 사용하여 블록을 종이 위에 눌렀을 때 구성의 거울 인상을 만듭니다(현대 미술관 비디오).

15세기 후반, 독일 예술가 Albrecht Dürer는 그의 지문에서 인상적인 질감과 색조의 미묘함을 묘사하는 방법을 찾았습니다. 일련의 가는 선들을 서로 가깝게 조각함으로써 삼손과 사자 , 그는 언덕의 그림자를 설득력 있게 표현했습니다.

이 인쇄물의 흰색 영역은 잉크가 묻지 않은 것입니다. 장면의 하이라이트 역할을 합니다. 루카스 크라나흐 장로, 세인트 크리스토퍼 , 씨. 1509년, chiaroscuro 목판화(클리블랜드 미술관, 클리블랜드)

<강한> 키아로스쿠로 목판화

다음과 같은 손으로 색칠한 목판화의 생산에서 알 수 있듯이 피에타 그리고 불의 마돈나 , 일부 수집가는 컬러 지문의 미학적, 감정적 음모를 선호했습니다. 16세기에는 북유럽과 이탈리아의 판화 제작자는 chiaroscuro 그림의 모양을 모방하기 때문에 chiaroscuro woodcuts로 알려진 컬러 목판 인쇄물을 만들어 그 관심을 이용했습니다. 이런 종류의 그림에서는 색종이는 작가가 흰색 물감을 더해 빛을 내는 중간톤 역할을 한다. 치아로 ) 톤을 더 어둡게 렌더링합니다( 스쿠로 ) 펜으로 해치 마크를 통합하거나 브러시로 짙은 워시 영역을 통합하여 값. 동일한 개념이 chiaroscuro 목판화에도 적용됩니다. 루카스 크라나흐 세인트 크리스토퍼 , 예를 들어, 두 개의 다른 목판으로 만들었습니다. 목판 하나, 톤 블록이라고 하며, 오렌지 중간 톤을 만들었습니다. 두 번째 목판, 라인 블록이라고 하는 검은 선을 생성하고, 그것이 기본 설계와 해칭입니다. 용지의 인쇄되지 않은 영역이 하이라이트 역할을 합니다.

의 예 흑금 플라크, 어두운 페이스트 같은 물질로 상감된 금속 표면에 절개된 선형 디자인이 있습니다. 헌신적 인 Diptych 출생 그리고 동경 , 씨. 1500, 파리, 프랑스, 은, 흑금, 금동 합금, 13.9 x 20.8 x 0.7 cm(클로이스터스 컬렉션, 메트로폴리탄 미술관)

<강한> 조각

최초의 목판화가 만들어진 지 얼마 되지 않아, 판화의 음각 과정은 1430년대 독일에서 나타났고 15세기 후반까지 북부 및 남부 유럽의 다른 지역에서 사용되었습니다(음각은 판화를 포함하는 판화의 범주입니다. 드라이포인트 및 에칭). 판화는 석판 인쇄와 같은 평면 기술이 발명될 때까지 18세기 말까지 판화를 위한 일반적인 방법으로 남아 있었습니다. 조각은 금세공과 은세공의 전통에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다. 흑금 플라크(금 또는 은으로 된 작은 판)는 금속 표면에 선형 디자인을 절개하고 새겨진 홈에 어두운 풀 같은 물질을 박아 명확한 표현을 제공하여 만들었습니다.

예술가들은 미세한 표면 디테일을 만들기 위해 금속판을 긁고 에칭했습니다(현대 미술관 비디오).

조각 과정에 사용된 Burins(사진:Manfred Brückels, CC BY-SA 3.0)

목판화의 부조화 과정과 달리, 조각은 부린이라는 마름모꼴 모양의 끝이있는 도구를 사용하여 동판으로 조각하여 생성되며, V 자 모양의 홈이 남습니다. 디자인을 완전히 절개한 후, 판의 전체 표면이 잉크로 칠해져 있습니다. 다음, 절단된 선에 침착된 잉크만 남도록 플레이트를 깨끗하게 닦습니다. 이제 매트릭스는 젖은 종이로 인쇄기를 통과할 준비가 되었습니다. 인쇄기의 압력은 용지를 그 홈으로 밀어 넣고 잉크를 집어들고, 결과적으로 동판에 새겨진 이미지의 거울 인상이 생깁니다.

이것은 Schongauer의 초기 판화 중 하나이지만, 엄청난 영향력을 미쳤습니다. 미켈란젤로는 심지어 그것을 복사했습니다. 마틴 쇤가우어, 악마들에게 고통받는 성 안토니오 , 씨. 1475년, 조각, 30.0 x 21.8 cm(메트로폴리탄 미술관)

양각 도안을 목판에 새기는 어려움에 비해, 조각 기술을 통해 숙련된 예술가는 기계식 인쇄기의 압력으로 인해 끊어질 너무 좁은 선을 생성할 염려 없이 매우 상세하고 문체적으로 다양한 구성을 만들 수 있었습니다. 르네상스 유럽의 가장 위대한 조각가 중 한 사람은 Martin Schongauer였습니다. 그의 악마들에게 고통받는 성 안토니오 그의 다재다능한 조각 기술을 보여줍니다.

마틴 쇤가우어, 의 세부 사항 악마들에게 고통받는 성 안토니오 , 씨. 1475년, 조각, 30.0 x 21.8 cm(메트로폴리탄 미술관)

다양한 질감을 연출하기 위해 Schongauer는 다양한 마크를 사용했으며, 긴 것과 같은, 악마의 부드러운 털을 표현하기 위한 컬링 라인은 곤봉을 휘두르는 짧은 U자형 라인으로 Anthony의 왼팔을 잡는 생물의 비늘을 만듭니다. By incorporating passages of dense cross-hatching across Anthony’s body, Schongauer also gave his figure a three-dimensional presence on the flat paper surface.

Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer, who created ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor. Attributed to Kolman Helmschmid, etching attributed to Daniel Hopfer, Cuirass and Tassets (Torso and Hip Defense), with detail of Virgin and Child on the center of the breastplate, 씨. 1510–20, steel, leather, 105.4 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

<강한> Etching

Another intaglio process that developed in Germany around 1500 and remained popular throughout the early modern period was etching. While engraving originated from the craft of gold- and silversmithing, etching was closely related to the armorer’s trade. Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer in Augsburg, a city in southern Germany. Hopfer discovered that through etching he was able to create ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor.

To etch an iron or copper printing plate, an acid-resistant substance (usually a varnish or wax) called a ground is applied to its surface. With a stylus or needle an artist draws a design into the ground, removing some of the coating each time a mark is made. After the design is complete, the plate is submerged into an acid bath and a chemical reaction takes place. The acid bites into the exposed metal, creating linear grooves. Once the plate is taken out of the bath and the ground is removed, the incised matrix is ready to be inked and printed in the same way as an engraving. Whereas engraving takes considerable manual labor because the printmaker has to carve into the metal plate, in the etching process, the acid does all of that work, and so it was considered an easier alternative to engraving. Artists who were adept at drawing, but not necessarily trained to engrave plates, found etching to be a suitable medium to make prints, since realizing a design in the ground with a needle was akin to drawing with a pen on paper.

Parmigianino, Entombment , 1529−1530, etching, 27.1 x 20.4 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland)

Just like engraving, which had originated in Germany but quickly became popular among artists in other parts of Europe like Italy, etching also spread throughout the continent soon after its development. Parmigianino was one early sixteenth-century Italian painter and draftsman who tried his hand at etching. 그의 Entombment shows off his expressive line work. It appears “sketch-like, ” resembling a pen-and-ink drawing rather than an engraving, which is usually characterized by regularized lines and marks of equidistant spacing and length.

First state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People , 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

<강한> Drypoint

Drypoint is perhaps the simplest method for creating an intaglio print. It developed at the same time as engraving in early fifteenth-century Germany, and like other related processes, drypoint attracted printmakers working across Europe. The technique involves using a stylus or needle to scratch into the surface of the copper matrix to throw up a burr. Just as the sides of a furrow or trench dug into the ground will hold drifts of snow, the raised edges of a drypoint line will retain ink. When making an engraving, the printmaker scrapes away the burr in order to achieve clean lines when the plate is printed. In a drypoint, however, the burr is left so that when the plate is printed, it produces a rich, velvety line. Unlike engraving, which can yield hundreds of decent impressions, the delicate drypoint burr wears quickly each time a plate is run through the press. 이러한 이유로, drypoint was most often used to add finishing touches to compositions after the primary design had been engraved or etched. 아직, some printmakers like the seventeenth-century Dutch master, Rembrandt, preferred to work entirely in this technique.

Detail, first state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People, 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

에 Christ Presented to the People , the contours of Pontius Pilate, Christ, and the surrounding soldiers reveal the dense, blurred character of the drypoint burr. Because drypoint created few quality impressions, Rembrandt often reworked his plates, making different states of the same image in order to produce more legible representations. The first state was printed early on in the plate’s lifetime before the burr began to wear. In the fourth state, the once-strong velvety lines have all but disappeared and changes to the architecture are visible. Most noticeably, the balustrade depicted near the upper right does not appear in the first state.

Fourth state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People , 1655, drypoint iv/viii, 35.8 x 45.4 cm (British Museum, London)

<강한> Mezzotint

Mezzotint rockers (photo:Toni Pecoraro)

The term mezzotint is a compound of the Italian words mezzo (“half”) and tinta (“tone”), and describes a type of intaglio print made through gradations of light and shade rather than line. To produce a mezzotint, an artist roughens the entire surface of a copper plate with a tool called a “rocker, ” a chisel-like implement with a semi-circular serrated edge. This tool is rocked back and forth across the plate until it has been completely worked, creating a surface full of burr that will hold ink. If you were to print an impression at this stage, it would appear as a field of rich black. To create a legible image, the printmaker must work from darkness to light with the aid of a scraper—a triangular-shaped blade fixed in a knife handle—and a burnisher—a blunt instrument with a hard, rounded end. By removing or smoothing out the burr, the artist weakens the plate’s capability to hold ink when the plate is wiped, and those areas will print a lighter tone.

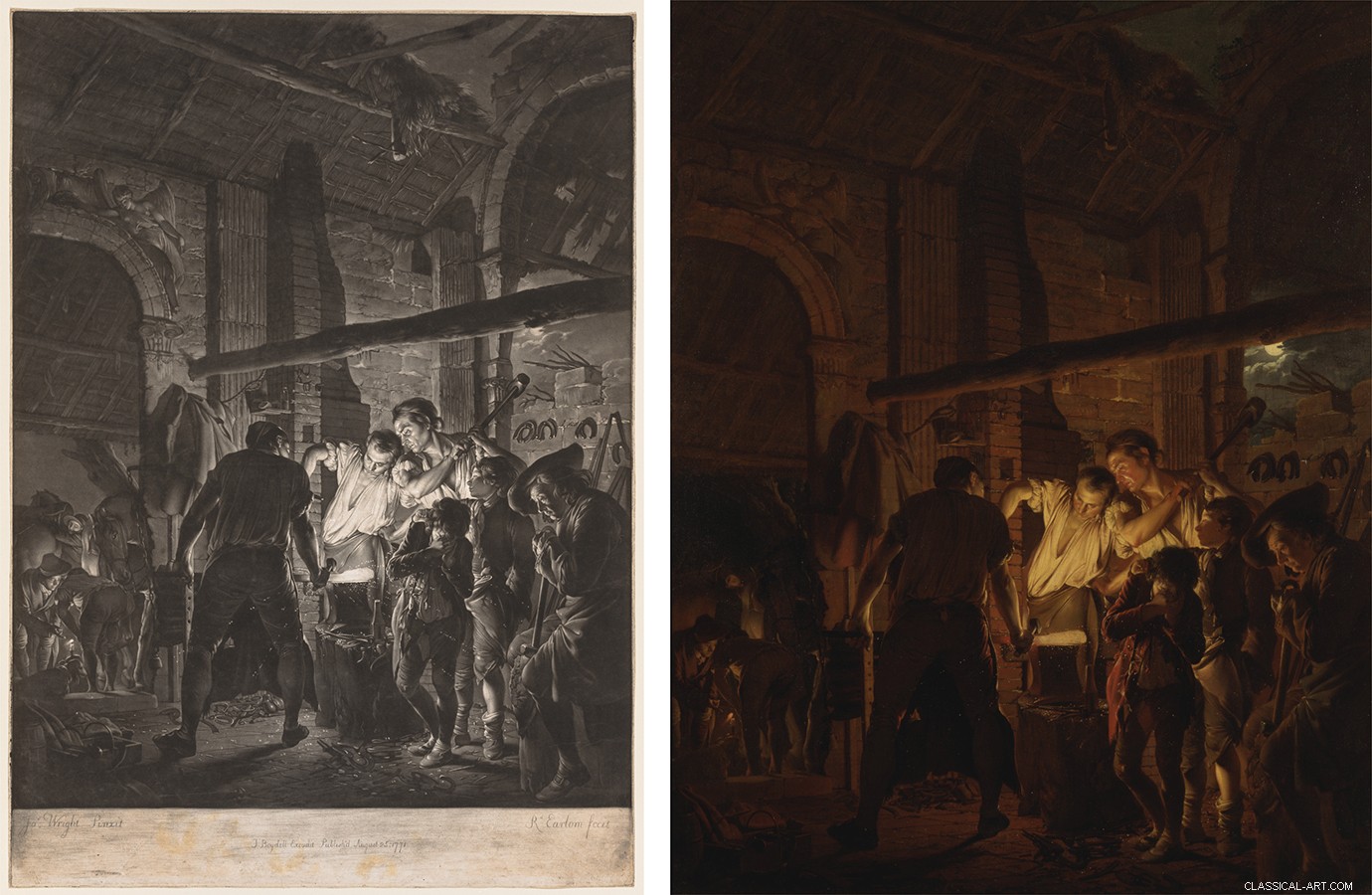

Left:Richard Earlom after Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop , 1771, mezzotint ii/ii (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland); right:Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop , 1771, oil on canvas, 128.3 x 104.1 cm (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven)

Although mezzotint originated in Amsterdam during the second quarter of the seventeenth century, it found particular appeal in eighteenth-century London, so much so that the medium was even nicknamed “the English manner.” When the Dutch-born sovereign William III became King of England in the late 1600s, numerous printmakers from the northern provinces of the Netherlands relocated to London in hopes of achieving royal patronage. During successive decades, native English artists learned from their Dutch contemporaries about how to make mezzotints and several technical manuals on the subject were also published locally. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, England had earned the reputation as a prolific center for mezzotint production. Richard Earlom was one English printmaker who had a successful career making mezzotint reproductions of oil paintings. The Blacksmith Shop from 1771 is based on Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting of the same subject. Wright’s pictures, which exhibit dramatic lighting effects, were ideally suited to be translated into mezzotint because the medium could capture the subtle tonal variations and lustrous appearance of his oil paintings.

<강한> Aquatint

Aquatint is a variant of the etching process that produces broad areas of tone that resemble the visual effects of watercolor. It involves the use of a powdered resin that is adhered to the plate through controlled heating. As the resin bonds to the plate, it creates a network of linear channels of exposed metal (think of how a cake of mud that is dried in the sun has a web of cracks). Once the plate is bitten by acid, the areas of exposed metal form deep grooves that are capable of holding ink.

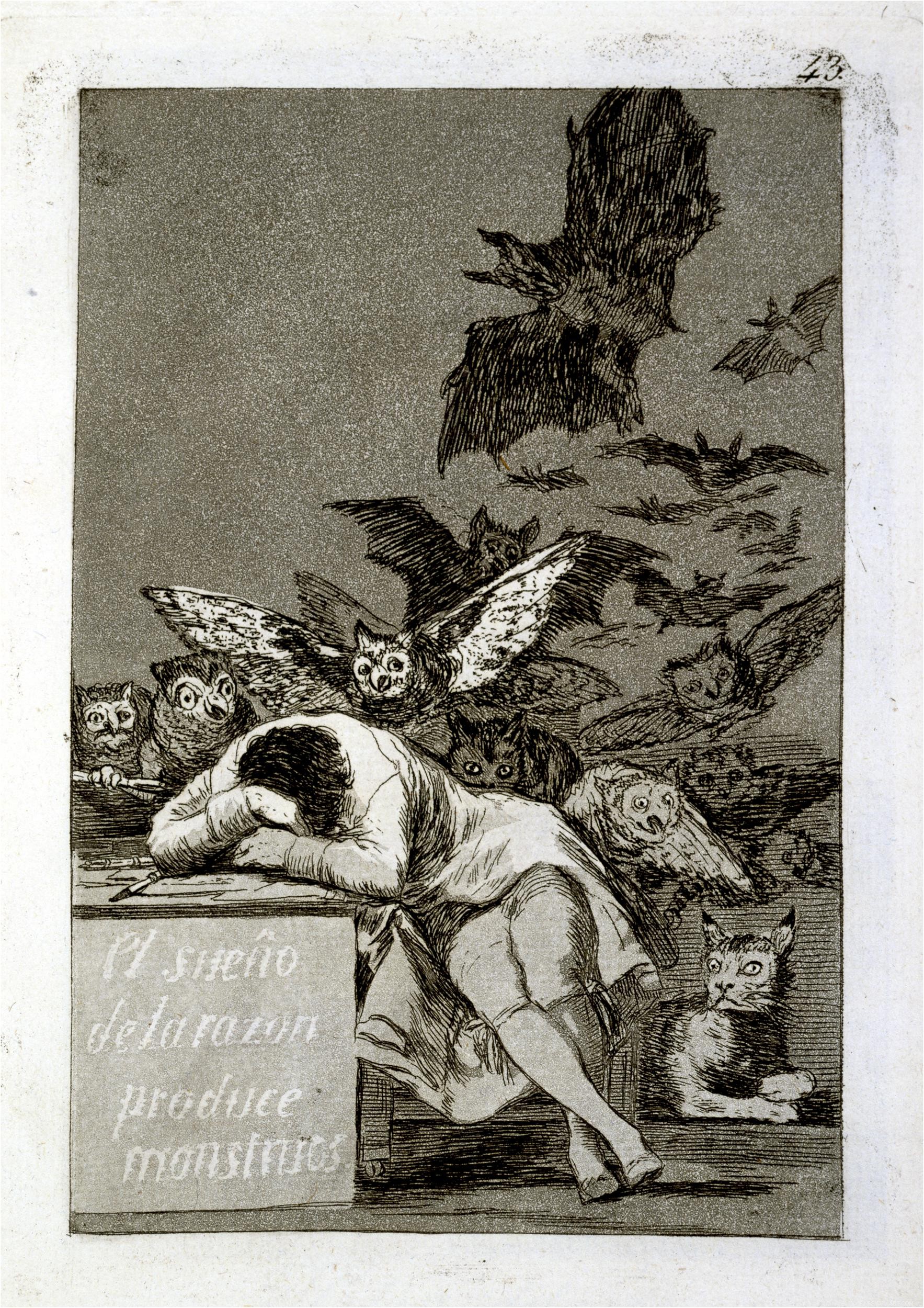

Francisco de Goya is famous for his artworks using aquatint. Goya, Los Caprichos:The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters , 1799, etching and aquatint, 21.2 x 15.0 cm (British Museum, London)

Aquatint was first introduced in the mid-seventeenth century in Amsterdam. 아직, unlike other printmaking techniques that found immediate attraction, it would take some time before aquatint became more widely used. By the late eighteenth century, several English etchers had become drawn to the more painterly qualities of aquatint, but the medium arguably achieved its greatest acclaim under the Spanish artist, Francisco de Goya. 만들다 The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters , Goya first etched his sleeping artist, the bats, and haunting cat with quick lines. From there, he switched to aquatint to render the ominous shadow that envelops the entire composition and the white letters on the front of the artist’s desk.

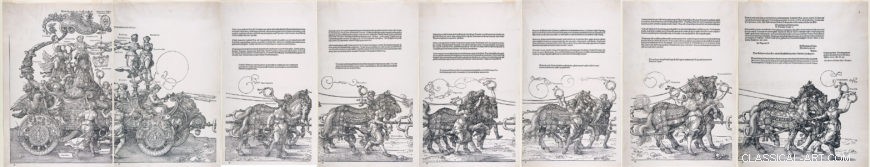

An example of a multi-sheet composition. Albrecht Dürer, Large Triumphal Carriage , 씨. 1518−1522, woodcut (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 뉴욕)

<강한> The business of printmaking

Printmaking in early modern Europe was a complex enterprise that involved a number of different agents. It was not always the case that the individual responsible for carving the woodblock or incising the metal plate was the designer of the composition. When Dürer was commissioned by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I to design a complex, multi-sheet composition of the Large Triumphal Carriage , he teamed up with a talented workshop of block carvers to help him execute that grand-scale project. In some workshops, the figure who undertook the physical process of printing the blocks and plates may have only done that job. 추가적으로, there may have been a separate position dedicated to print publishing, that is selling and distributing the prints. Depending on the size of a workshop and the equipment available, some printmakers or publishers had to contract out some of those tasks. 예를 들어, if a publishing shop did not own a press, it had to collaborate with another local shop to produce its prints. Early printmaking revolved around a sophisticated network of artists and businessmen, and this legacy is still seen today. Many contemporary printmakers partner with a printing shop to create their work and/or a commercial gallery to exhibit and sell their art.

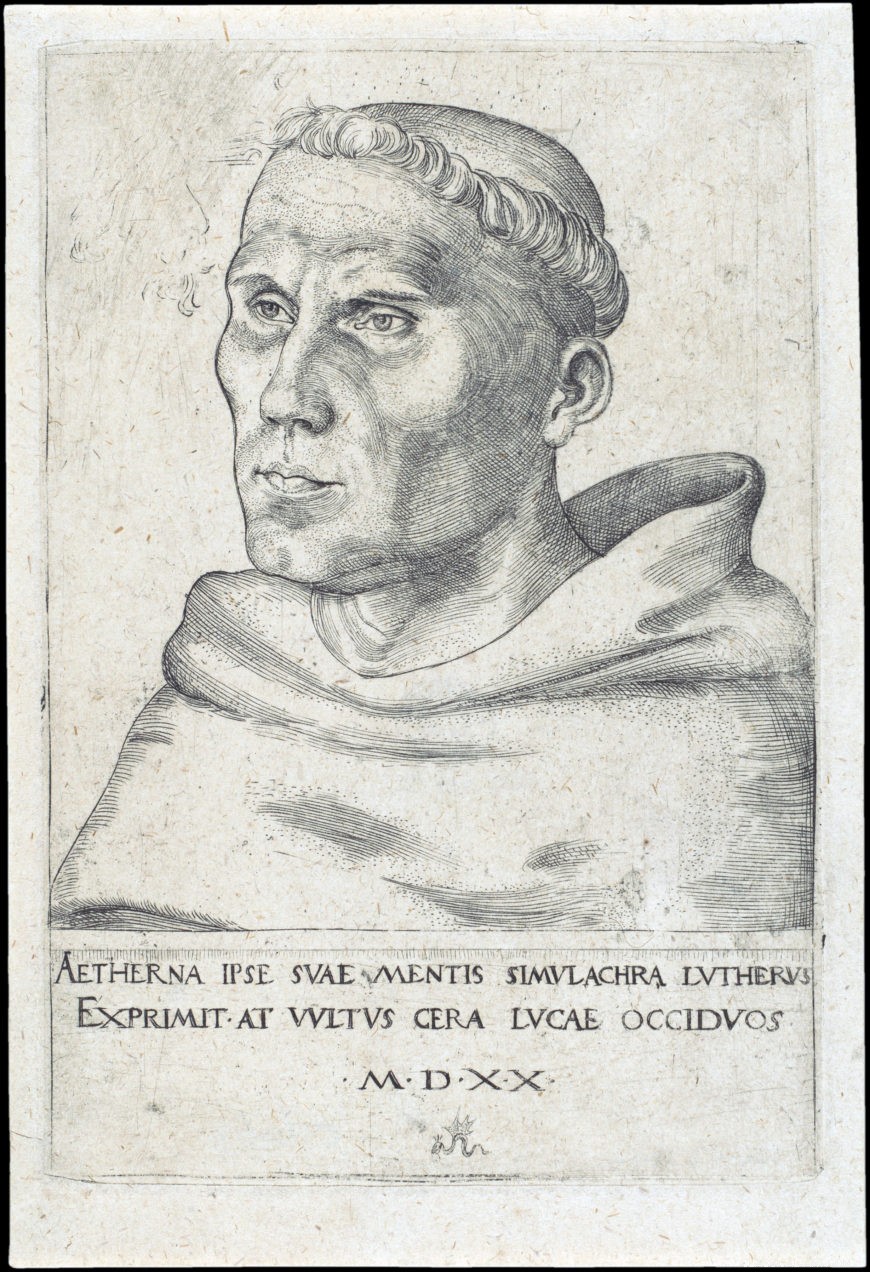

Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk and professor of theology in Wittenberg. He posted his 95 Theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg—at least, this is how the tradition tells the story—that took issue with the way in which the Catholic Church thought about salvation, and it specifically took issue with the selling of indulgences. Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk , 1520, engraving, 15.8 x 10.7 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The advent of print not only transformed how images were made, but it created new possibilities for art collecting and mass communication. Scholars have long recognized how the mass distribution of printed pamphlets criticizing the Roman Church’s sale of indulgences and the pope’s supremacy along with printed portraits of Martin Luther, such as Cranach’s Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk , spurred on a religious revolution in northern Europe by promoting the agenda of Protestant Reformers.

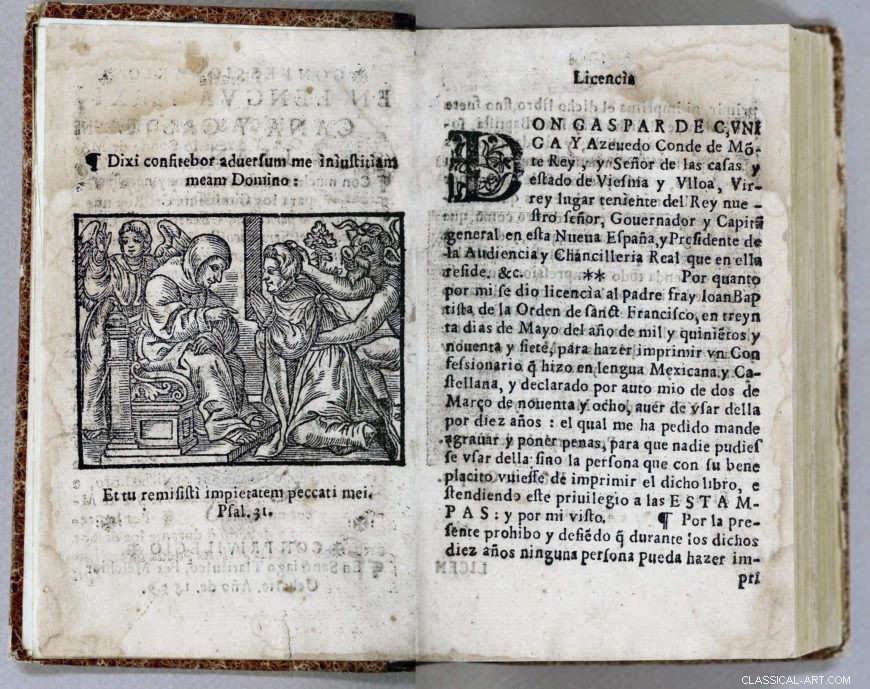

Books made in early colonial Mexico often stressed the importance of images in the process of converting Indigenous peoples. Juan Bautista, Confessionario en lengua mexicana y castellana [Preparation of the penitents in Nahuatl and Spanish] (Santiago Tlatelolco:Melchor Ocharte, 1599), 1v–2r (John Carter Brown Library)

The portability, reproducibility, and affordability of printed compositions contributed to the exchange of information and ideas between cultures of distant geographies. European missionaries who journeyed to the Americas beginning in the sixteenth century brought with them prints of biblical figures that were subsequently disseminated among Indigenous populations in an effort to convert those local communities to Christianity. This kind of imagery also introduced Indigenous artists to new iconographies, visual traditions, and technologies that greatly impacted the artistic production in the Americas. 사실로, during the mid-sixteenth century, the first printing shop was established in modern-day Mexico City and a few decades later Peru transformed into another important center for printmaking in the southern hemisphere. What we consider to be “mass media” today, certainly has its origins in the early modern world of printmaking.